The data analyses from my last two posts, How Many Angel Investments? and What If the Angel Market Tanks?, have an important alternative interpretation. If you also read my earlier posts on diversification in general, Diversification Is a “Fact” and Even If You’re “Good” Diversification Matters, you may have an inkling of what’s coming. The punchline is:

For angels, diversification can be more important than skill…

(… at the margin, if all you care about is returns, and you have typical risk preferences.)

I know what some of you are thinking: “Oh, you’re one of those crazy ‘spray and pray’ guys who don’t think you need to learn anything about a company to invest in it. Don’t you know angel investing takes a lot of experience and time?”

Before you write me off as a loon, please give me just a few more seconds of your time. That’s not actually what I’m saying. There are some rather crucial nuances and disclaimers. Moreover, the analysis we’ve already done with the AIPP sample of actual angel investments clearly supports my nuanced and disclaimed position.

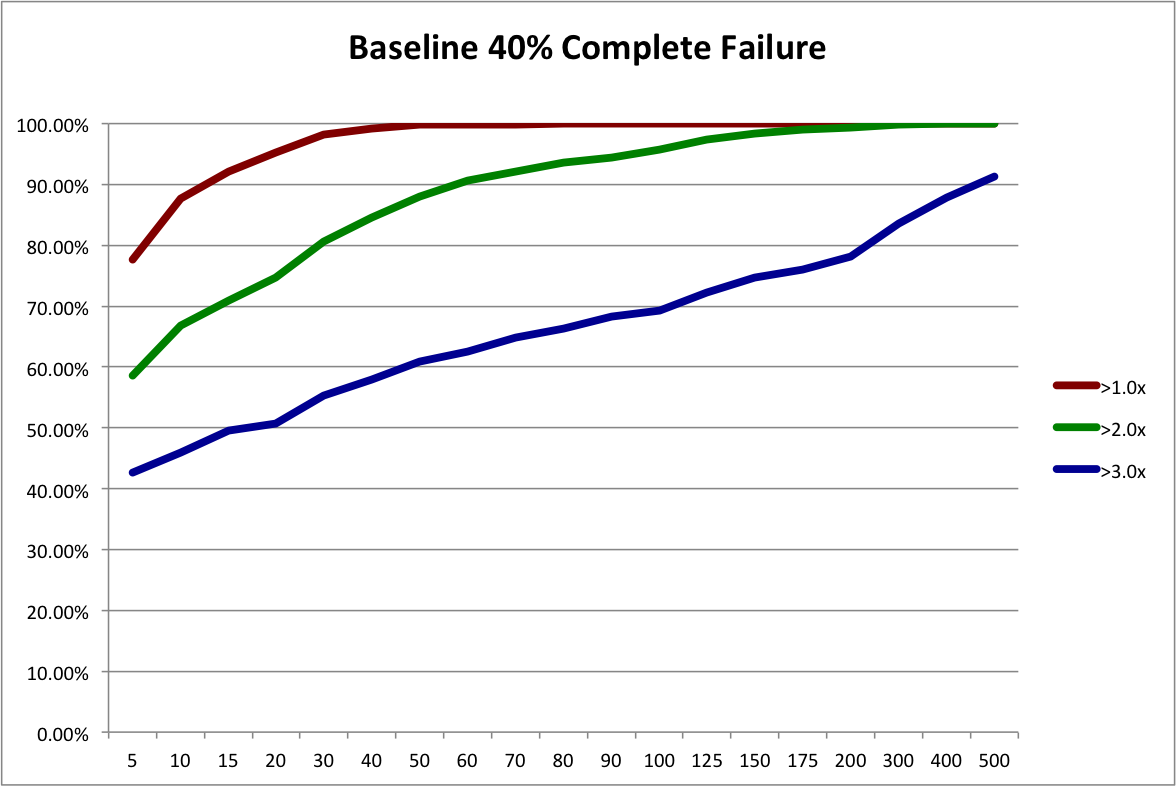

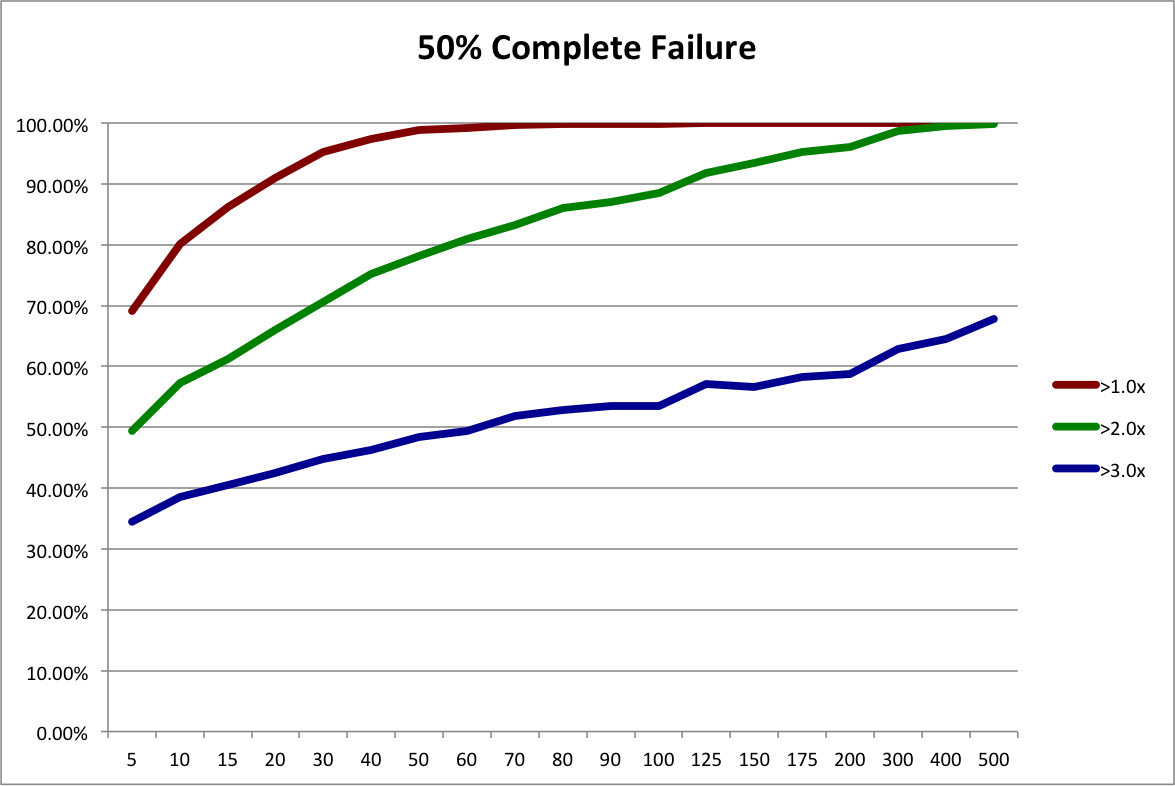

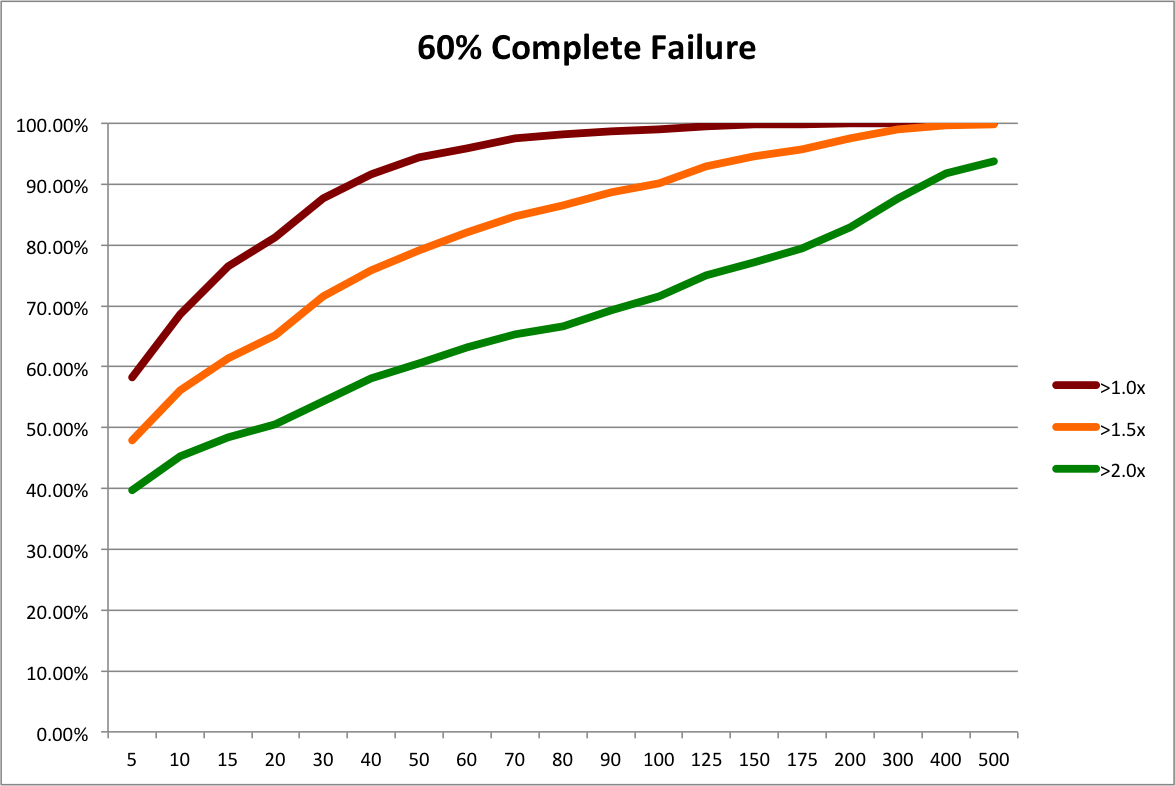

First, let’s reinterpret the “50% Complete Failure” scenario from the last post. Instead of looking at it as a possible future scenario for the angel market as a whole, let’s look at it as the possible future outcome distribution for a slightly different investing strategy, “Scalable Angel”.

This hypothetical strategy contrasts with the traditional investment strategy, “Custom Angel”. Using the Custom Angel strategy, individual angels and angel groups apply their substantial experience to perform a lengthy personalized screening and evaluation of each startup investment opportunity. While very thorough, this strategy is not very scalable. It requires years to develop the necessary skill and a considerable amount of time to apply.

The Scalable Angel strategy is based on the Custom Angel strategy. However, it eliminates many screening and evaluation tasks that can’t be boiled down to policies, templates, and heuristics. It still applies a lot of screening and evaluation. It even applies a fair amount of personalized attention. It just avoids the lowest-value and most time-consuming steps. While definitely more scalable, a lot of people may find it hard to believe that it could be as effective.

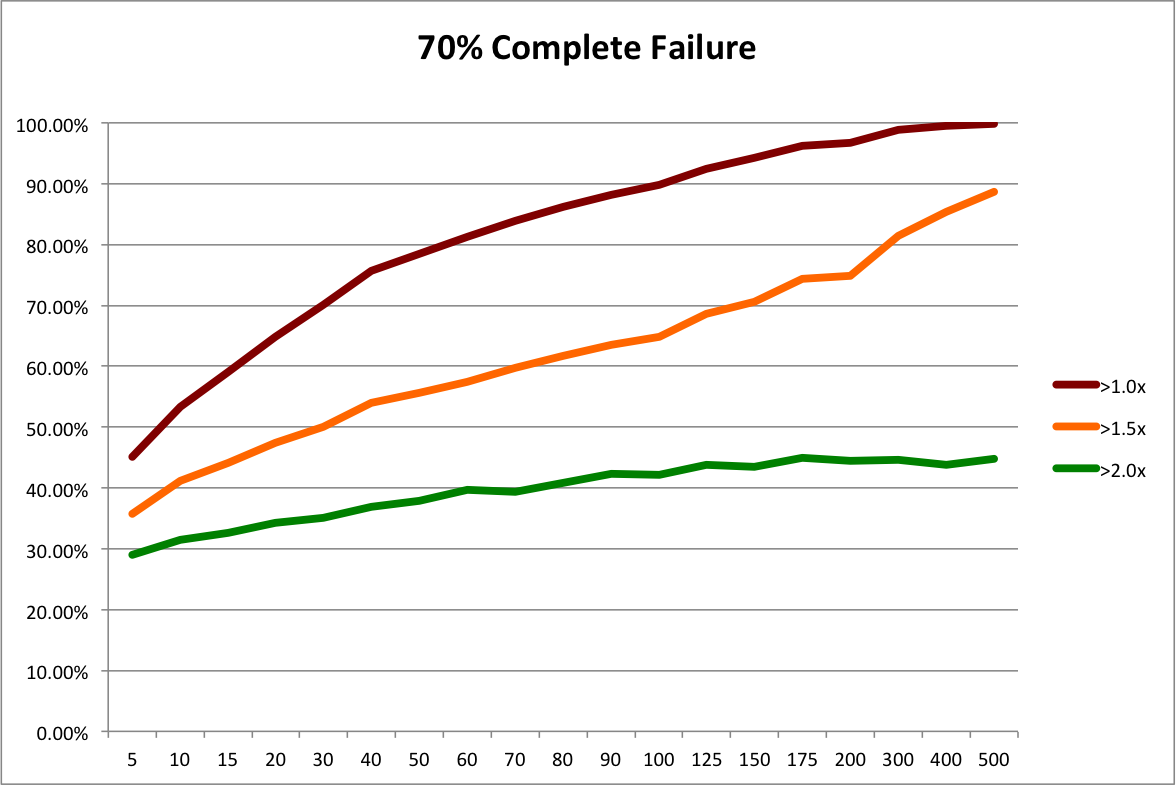

So for the sake of argument, let’s assume that it’s not nearly as good as the Custom Angel strategy and results in 50% more failed investments. The “Baseline 40% Complete Failure” scenario from the last post had 111 failures, while the “50% Complete Failure” scenario had 166, which is 49.5% more. So, conveniently, we can use the resampling of 50% Complete Failure to represent the outcome distribution for the Scalable Angel strategy.

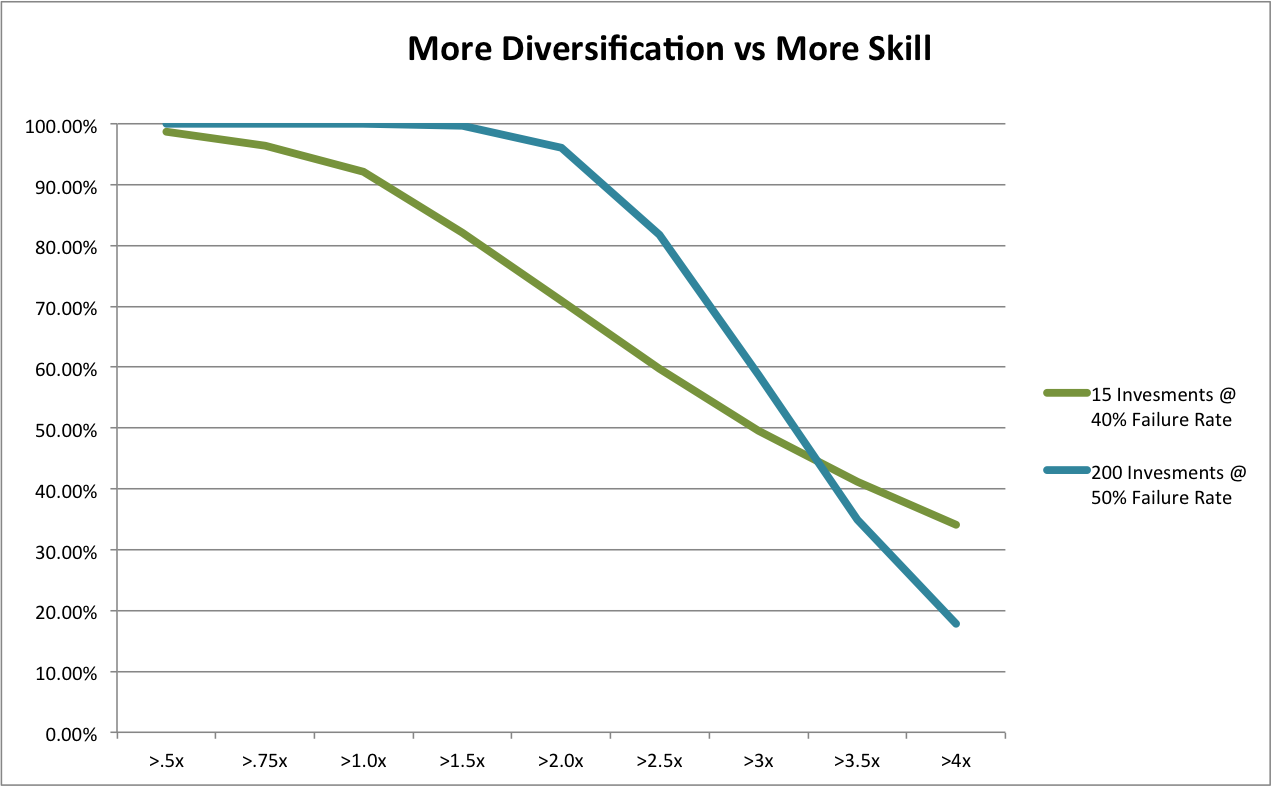

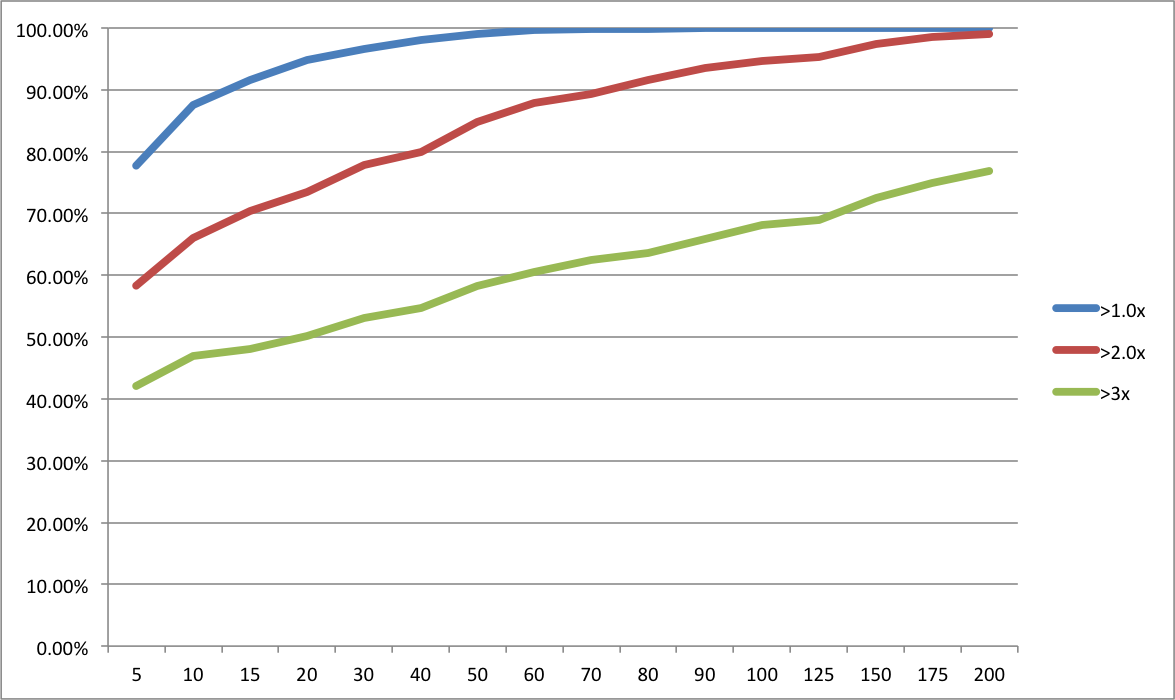

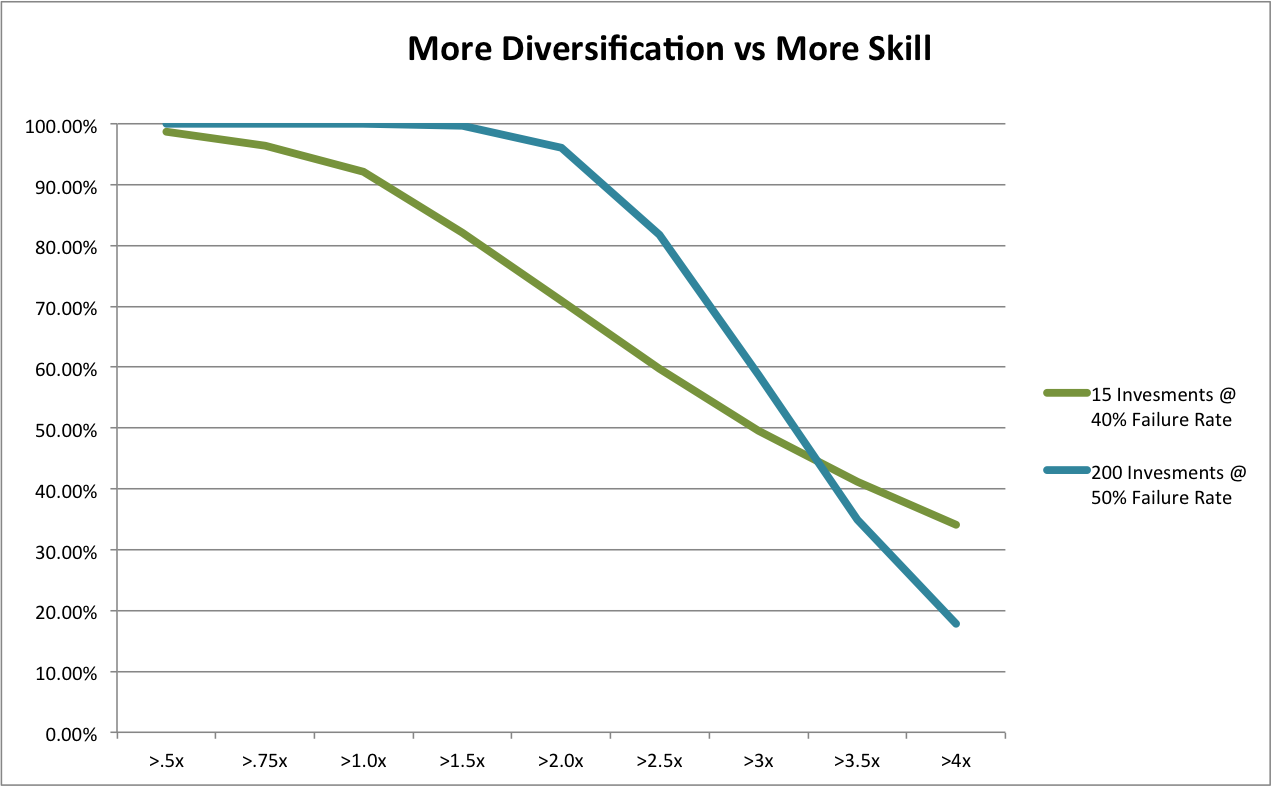

Now, all we have to do is decide on reasonable portfolio sizes to compare. In the original Rob Wiltbank Tech Crunch article that kicked off this series of posts, he recommended “…at least a dozen investments…”. To give Custom Angel the benefit of the doubt, let’s use 15. My anecdotal experience is that a 15-investment portfolio would put an angel in the “very active” category. On the other end of the spectrum, RSCM (my firm) is aiming for 250 investments in its fund and, as Dave McClure so kindly contributed in the comments of the last post, 500 Startups will have about 250 investments per fund. But let’s again be conservative, so we’ll use 200 investments for our hypothetical Scalable Angel strategy.

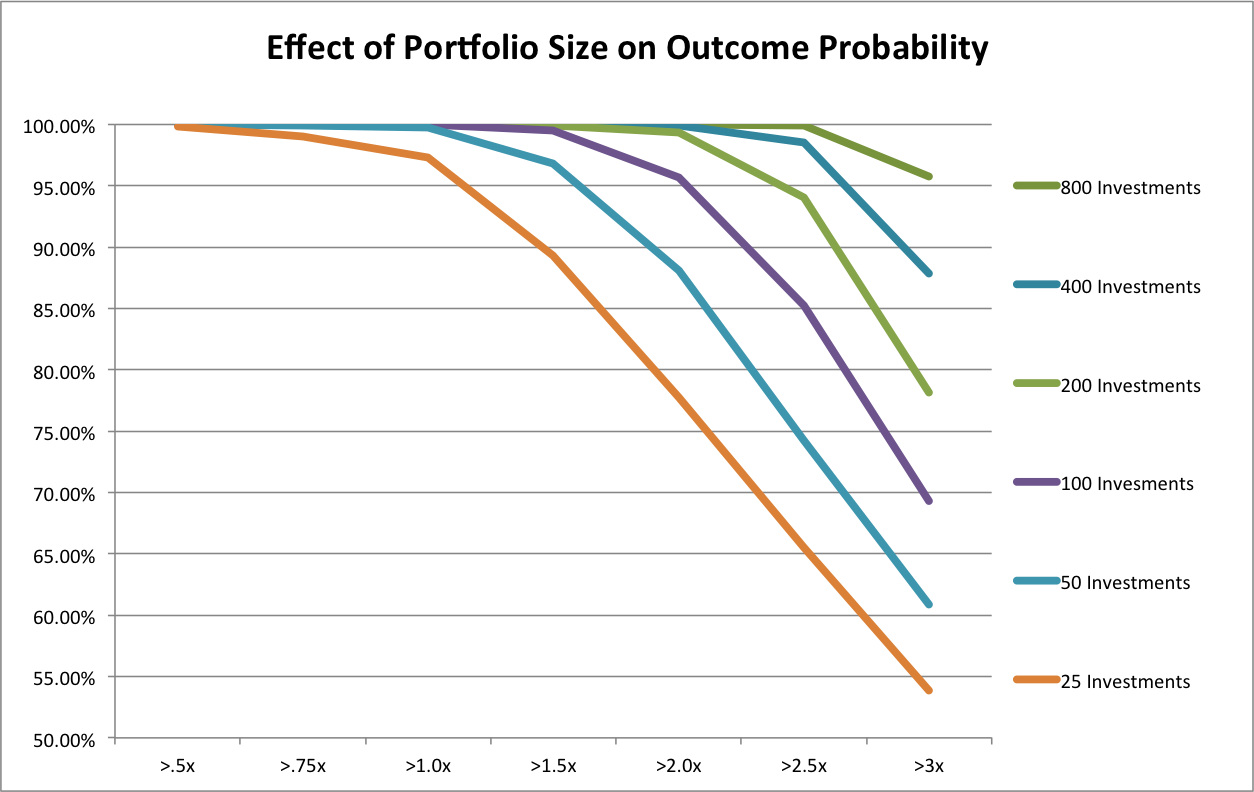

It’s a simple mater to look at the last post’s spreadsheet and plot the probabilities of achieving different return multiples using the two strategies:

Due to our assumption of a much higher number of failures, Scalable Angel has a lower expected value, 3.66x vs 3.24x. But is sure looks a lot safer overall! Scalable Angel did not have a single losing portfolio out of 10,000 simulations while almost 8% of Custom Angel portfolios lost money. Scalable Angel has a whopping 24 percentage point advantage in doubling your money (95.17% vs 70.98%). Even at tripling your money, where its lower expected value starts becoming apparent, it has a 9 percentage point advantage (49.61% vs 58.32%).

What about those nuances and disclaimers? Well, Scalable Angel certainly does not assume we can costlessly eliminate screening and due diligence. It assumes we can either streamline or find streamlined substitutes for many, but not all, aspects of screening and due diligence. For those we can’t, it assumes we pay a pretty hefty penalty of 50% more complete failures.

Also, it assumes that angels are interested only in overall returns. Individual angels and angel groups may be legitimately concerned with the failure rate. If part of why you like being an angel is the feeling you get from helping a company succeed, I would certainly understand wanting to maximize the number of successes even if that resulted in greater financial risk (especially if you were risking a very small fraction of your overall wealth). On the topic of risk, our conclusion further assumes angels are willing to sacrifice a bit of return on the high end for a much lower chance of suffering outright losses or even under-performing the public equity market. While individuals certainly differ, the empirical literature on risk preferences (nicely summarized here) supports this assumption for typical investors.

On the other hand, our current analysis also ignores some likely additional advantages of the Scalable Angel strategy. First, when you make a process more systematic, you usually reduce per unit costs. The AIPP data, indeed angels in general, do not track investment costs very precisely. My anecdotal experience is that a fair accounting of angel out-of-pocket and labor expenses would put them at a noticeable fraction of the dollars they invest. By ignoring these expenses, the AIPP data overstate the return of the Custom Angel strategy. Like any high-efficiency process, the Scalable Angel process would probably cut these costs dramatically, increasing its true relative return.

Moreover, high-volume processes tend to be more measurable than custom ones. Greater measurement leads to greater optimization. That’s the point of the whole “Big Data” trend! So even if the Scalable Angel strategy were initially less effective, over time, I bet it would close the gap in the expected failure rate, probably eventually surpassing Custom Angel.

Finally, I don’t think Scalable Angel would actually have a substantially worse outcome distribution. If you saw Moneyball, you know that some relatively simple metrics outperformed all those experienced baseball scouts performing their individual player evaluations. In this old post, I present the strong empirical evidence against individual’s ability to predict success when a startup launches. Now, ongoing individual attention probably provides some benefit to a startup’s development. But in practice, RSCM and 500 Startups provide quite a bit of this type of guidance. If you performed a detailed comparison of this assistance vs the typical active angel’s assistance, I think it would be hard to argue that the difference would lead to 50% more failures.

So I think it’s pretty safe to say that our hypothetical Scalable Angel outcome distribution is an extremely conservative comparison to past practice. And it still clearly outperforms in terms of risk-reward. From the perspective of angel investments as investments, the evidence strongly supports scalable approaches as a competitive option.

[Updated 4/25/2013: corrected minor error in spreadsheet and graph.]